A radio programme on the match of the century took place last August. I was invited, but some practical difficulties meant that I had to limit my participation to a text, which was -- partially -- taken into account. Here it is in full.

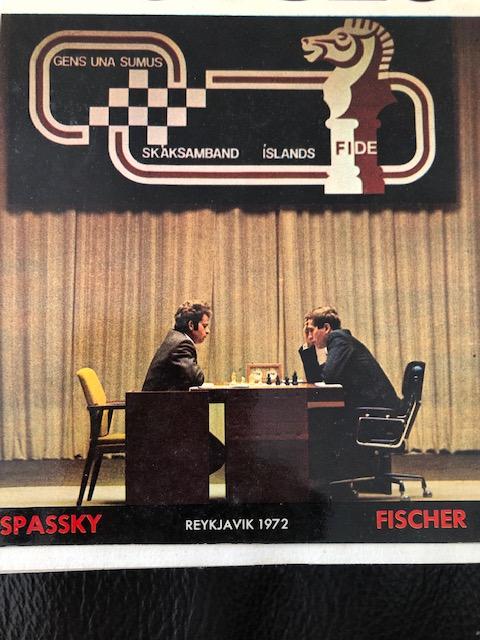

Match of the century (Reykjavik 1972)

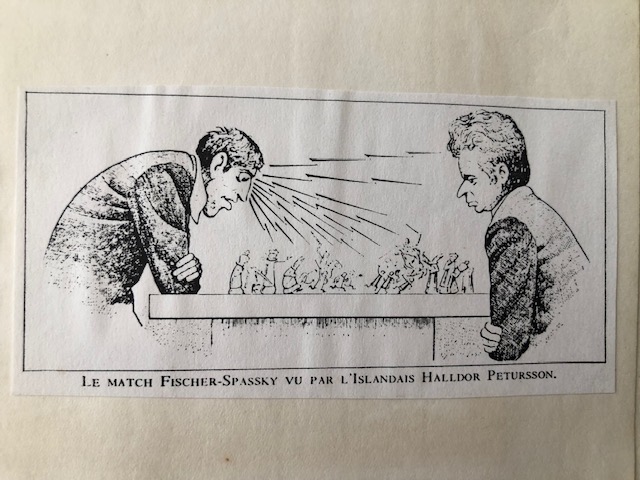

The 1972 Spassky-Fischer match was certainly the most publicised world championship of the 20th century. This was because it was the first time that a single man from the United States had faced the terrible Soviet machine, which had held the title since the Second World War.

The political aspect was yet secondary: this was not a "capitalism versus communism" or "new world versus old continent" match! Fischer had little interest in politics (although Kissinger personally asked him to play), had a Hungarian father and a Polish mother, and therefore felt rather European. He had also spent a long time in Russia, meeting the best players there. For his part, Spassky had always been an anti-communist, rather close to Solzhenitsyn, whose absurdity he noted, as he did, in the French slogan "liberté-égalité", these two terms being antinomic, which indeed a moderately gifted schoolboy can understand. Moreover, he did not particularly want to keep his title, considering the state of world champion to be very uncomfortable (see quotes below). He also knew that Fischer, whom he had known since at least 1960 and deeply esteemed, was now the best. He was prepared to concede the title to him, but still put up a respectable fight. Of course, winning by forfeit, as the Kremlin masters suggested, was horrifying to him.

The whole world was watching the match, with masters commenting on it live, or rather slightly delayed (no question of the Internet!). I was playing in a tournament in Catalonia and the analyses went on until the middle of the night, to the point of forgetting our own tournament.

Game 1: the 29th move, where Fischer captures a pawn with a bishop, which we guessed would not come out of this mess, traumatised the whole world.

Some claimed that Bobby had not calculated far enough! Nonsense. He knew perfectly well that this move gave him no chance of winning, only... a chance of losing, although he was not a losing in himself. He simply wanted to keep the game going, as it seemed to be heading towards an insipid draw. By this initiative, he gave life to the game. Didn't he often repeat, not that "Chess is like life", but more exactly: "Chess is life"?

This is how this game became one of the most analysed in the history of Chess. The best players of the world broke their teeth there. It was believed that the decisive fault was at the 37th, at the 40th... but it seems that the only real fault was at the 39th (39...f5?). Nearly 50 years later, the analysis engines are still stuttering, as their horizon effect does not allow them to detect a fortress occurring long afterwards (Pa5 & b6 and a black-squared bishop against Pa6 & b7, draw, when it is won with the a5 pawn on a4 *). Both players, but especially Bobby, have created an artistic masterpiece, savoured for decades by all endgame enthusiasts.

Game 2: Forfeit win for Spassky. It was repeatedly said that Fischer's demands, especially concerning the presence of cameras, were intended to "destabilise" (a fashionable term) his opponent. Nonsense! His own "stability" was shaky, given the terrible challenge he had set himself. But never in his life did he try to disturb the concentration of an opponent. "I don't believe in psychology, I believe in good moves", he said.

Game 3: played in an adjoining room, without cameras, at Bobby's request. Spassky's first defeat against an opponent he had beaten in 1960, 1966 and 1970 with White, and drawed twice with Black. He was criticised for bowing to Bobby's demands. Of course, he saved the championship, smartasses!

Much nonsense about the 11th move (11...Nh5!). We are told that this move is surprising because a knight is badly placed at the board. A 5 year old child understands that he has only 4 squares available, instead of 8 if he is located in the centre. But if he is at the board, it is to re-centre himself shortly afterwards. And let me explain how a Knight on f6 can go to f4 otherwise, when d5 is unavailable. One of the main opening systems, invented at the beginning of the XXth century by Chigorin, places the Knight symmetrically on a5. Thousands of players have played it over and over again, proving its perfect validity.

We are then told that this Knight can be captured by a Bishop, leading to a deterioration of the black pawn chain. Certainly, but this Bishop also has a value, of which it is unpleasant to be deprived. The worst thing is to hear this idea presented as a provocative novelty, whereas this stratagem dates from the 1950s, practised by Boleslavsky who was then the 3rd player in the world. And Fischer, who read everything, even 19th century magazines, was obviously aware of it. In this case, he did not invent anything. His genius is enough, without the need to add to it.

Game 5: After a good reaction from Boris in the 4th, where all of Bobby's defensive science was needed, a weak performance ended on the 27th move with an horrible blunder.

Game 6: Surprise in the opening, Bobby abandoning the usual king-pawn for the Queen's bishop pawn. This was not, however, as has been said, the "first time" he had played it (see Palma 1970 against Polougaievsky). A model game where everything seems to flow: Chess seems suddenly easy! At the end of the game, Boris will applaud his opponent. Imagine for a moment Kasparov applauding Karpov... You know what I mean.

Game 8: new vice, also with the Queen's Bishop pawn, but Black answers symmetrically.

Game 10: back to the King's pawn for further torture. This makes, apart from 3 draws, 5 wins in a row for Bobby. The second half of the game will be more balanced.

Game 11 : Boris' reaction, which will be his 2nd and... last victory. Bobby's favourite "poisoned pawn" variation (...Db6xb2), which he had played in the 7th game. A very dangerous opening, designed to bring a full point by avoiding any flattening. But usually used against much weaker opponents. This time he hits the nail on the head.

Game 13: new surprise by the adoption of the "Alekhine defence", a weapon known to win, again, against less prestigious players, because it avoids simplifications. But a rare weapon in the world championship. A long game followed, with an incredible endgame where Bobby played for the win while his rook was locked up, so that he had 5 pawns (3 of them linked) against, in short, rook and bishop! It took a blunder on the 69th move for Black to win. Let us point out that one could save oneself, not only by 69 Rc3+ as all repeated, but also by 69 Rf1 (**).

Game 17: as for the 13th, a rare bird, the Pirc (pronounced "pirts") defence. White will capture the advantage, but it will follow a rook vs. knight and pawn endgame (the "exchange" advantage, as we say) where Boris will not be able to pierce the Black defence.

Game 21: an unambitious start, an advantageous black endgame, an erroneous "envelope" move that accelerates the defeat. Boris is tired and eager to congratulate the new hero.

* See "Les Finales" Volume 2, 1998 edition, page 132.

** See "Les Finales" Volume 1, 1998 edition, page 341.

"In my country, at that time, being a chess champion meant being a king. But when you are a king, you feel that you have a lot of responsibility, and there is nobody to help you" (B. Spassky).

"When I won the title, I was confronted with the real world. People don't behave naturally anymore: hypocrisy is everywhere" (B. Spassky).

"I give 98% of my mental energy to chess. The others give only 2%" (R. Fischer).

"Is it true, Lajos, that you work on chess eight hours a day? -- Why do you ask? People say that you yourself work eight hours a day. -- But they think I am crazy" (conversation between Fischer and Portisch).

"Fischer's return is a myth, it makes a good suspense for those who know nothing about chess. Fischer is from the past. He stopped because he never wanted to play again. To talk endlessly about his return is just a day dream" (G. Kasparov in 1987, as always well inspired -- we know that our two heroes played a re-match in 1992).

"Fischer was an individual and so am I. Nowadays, players have coaches, doctors, cooks, psychologists and parapsychologists. The championship has become a fight between two big collective farms" (B. Spassky).

"One day you teach your opponent a lesson and the next day he teaches you a lesson" (R. Fischer).

"Soviet chess school : a nonsense, of course... I believe there are national chess schools, but not ideological chess schools. There is rather a Jewish mentality, a Russian mentality, a German mentality, etc. [...] The press likes certain stereotypes. For example, the slogan of the French revolution was "liberté, égalité et fraternité". Yet these ideas are perfectly contradictory: if there is "liberty", there will be no "equality". But this is the kind of stereotype people like, so there will be a Soviet chess school and a fascist chess school! (B. Spassky).

"Fischer is neither diplomatic nor complacent. Rightly or wrongly, he has kept his convictions and principles intact for thirty years. Kasparov finds it hard not to contradict what he said last Tuesday" (E. Winter).

"Fischer was a gentleman, never a chess player had any objections to his conduct. Only organisers! I did my best to give him the best publicity in the world, saying and repeating that he is and remains the best player" (V. Kortchnoi).

"Fischer never allows his pieces to interfere with each other. He always looks for, and if necessary creates, empty spaces for them" (M. Euwe).

"I have a wife and children. Who will feed them if I die prematurely?" (G. Barcza declining Fischer's offer to analyse their game of... 97 moves in Zurich 1959).

Comments

1 Alain On Sunday, june 08, 2025

2 Alain On Tuesday, april 12, 2022